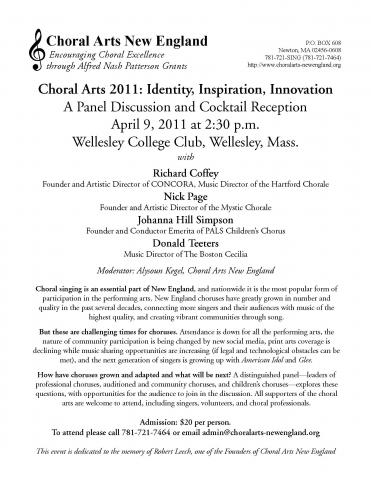

Choral Arts 2011: Identity, Inspiration, Innovation—A Panel Discussion and Cocktail Reception

Held the afternoon of April 9, 2011, at the Wellesley College Club, Wellesley, Mass.

Panelists

- Richard Coffey, Founder and Artistic Director of CONCORA, Music Director of the Hartford Chorale

- Nick Page, Founder and Artistic Director of the Mystic Chorale

- Johanna Hill Simpson, Founder and Conductor Emerita of PALS Children's Chorus

- Donald Teeters, Music Director of The Boston Cecilia

Moderator: Alysoun Kegel, Choral Arts New England.

Given below are audio recordings of the proceedings and transcripts of the panelist remarks (or jump directly to Teeters, Coffey, Page, or Simpson). Click to view or download the program for the event.

Audio filesClick on the title to hear (or download) the MP3 recording.

|

Transcripts

Transcribed by Peter Pulsifer

Donald Teeters

First of all, a little bit of self-promotion, because choral conductors are good at that! I’d like to introduce myself by saying that I am the conductor of Cecilia, but I am not the founding conductor of Cecilia. I need to tell you that a week from today, at just about this time, Cecilia has organized a benefit concert for the Japan earthquake and tsunami victims. It’ll be at Trinity Church, and it’s a Faure program, the Cantique de Jean Racine and the Requiem. Barbara Bruns, my longtime associate is going to play Bach’s last chorale, Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein, the last piece that Bach wrote, which he had to actually dictate the notes for—so I’ve been told. That will start at 3:00, and all the proceeds go to Japan. Everything has been donated. The Boston musicians’ association has allowed us to recruit an orchestra without paying them—that’s revolutionary in itself. We have members of choruses from all over. And I’m conducting. It’s quite a special event. The soloists are Jessica Cooper and Bob Honeysucker.

So! Now I’m supposed to talk about the history of choruses in New England. First of all, people have sung forever. Some of you will know more about some of this stuff than I do, because maybe you preceded me by a few years. In New England, at the very earliest stages, there was some kind of group singing going on—psalm singing. From what I read and have studied about it, probably the people who were singing it are probably not people you would really aspire to have in your chorus today, because I think it was more rough and tumble kind of singing.

In the 19th Century, choral music blossomed all over Europe and America. Very very large choruses were born. Sometimes 1,000 people, sometimes more than 1,000 people, singing Handel—Handel! But it’s all good, because in Boston, audiences were being exposed to music they didn’t know–“antique” composers, so-called—Bach and Handel, for instance, who were “antique”. B.J. Lang, the founder of Boston Cecilia, premiered literally hundreds of works of his time. Works of the late 19th century, of course, were more easily digested by the ear than contemporary works today. So he was giving the public what the public was eager to hear—new music by composers, many of whom they knew, because they lived in Boston and were New England composers.

In the 19th century, there were two significant choral establishments in Boston: Handel and Haydn, from 1815, and Cecilia, from 1876. Incidentally, I have here this beautifully bound volume, of all the programs from the first seven seasons of Boston Cecilia, 1877–1883. It’s beautifully bound and actually I’m going to circulate it. I only made one copy, but perhaps you could pass it around, just to see an example. That’s printed at size—they were these tiny little programs with lots of information, they must have had very good eyesight. It’s fascinating to go through that book. B.J. Lang, the founder, loved Schumann, so the first two or three seasons saw The Paradise and the Peri and Scenes from Faust and other works. Some of the programs were composites, lots of little bits and pieces here and there, May songs by various people, and some by composers of the period whom no one would recognize now.

Handel and Haydn was the big guy in town: they often sang with 500 or more singers. Cecilia was the small chorus, of about 250 in the 19th century. As the 20th century unfolded, things changes, and I’m sorry to say I think both groups in the first half of the 20th century fell into a bit of a slump. Administrative leadership was probably not as aggressive as it should have been, and the singers were allowed to grow older and older and older. Now, there’s nothing wrong with growing older, but this instrument tends to tire after a while (unlike conductors, who never...).

But the whole situation changed with World War II. After the war, we had this surge of people coming into Boston—men primarily, who’d had to defer their education for three, four, five, six years in some cases. So the schools were filled to overflowing with not 18- or 20-year old men, but men who were 24, 25, 26. And those were mature voices, unlike most collegiate voices, then and now. So there was this impetus to use these men, and there have always been fine women singers around.

Bud Patterson took advantage of that. He formed the Chorus pro Musica, as we were told, in 1948 or 1949. I think he was organist at Christ Church in Cambridge when that group was organized. It was absolutely unique, and remained unique in many respects throughout his tenure. Bud was extremely musical and he was wonderful at teaching music. He could be a little crazy. I remember a performance of the Matthew Passion which we did at Symphony Hall and we came to a stopping point in the program, just a brief break, and I turned to the cellist, who I think was Corine Flavin, and I said, have we ever seen this next movement before? She said, I haven’t. So sometimes we would go into concerts, and you people who were members of the CpM, will appreciate and actually treasure some of those high-wire acts that you accomplished by being part of Bud’s original group. And they were very exciting times.

I was hired by Bud in 1963 or 1964 and worked with him for three or four years until I went to work with Handel & Haydn when Tom Dunn came to Boston. But they were very exciting years with Bud. I’ll tell you one little anecdote about a concert that was more embarrassing for me than for anybody else. We were doing a concert in Kresge auditorium at MIT. If you’ve been there, you know that the organ is exposed, way up on the right-hand side. We had a rehearsal the day of the performance; everything was all set and I was a little nervous about being so exposed, so when I left the organ I had every stop pulled, everything was all set so when it came time to come out I could just put my fingers down on the keys and get sound. Well, the chorus came on, the conductor came on, I sat down at the organ, and he gave of Bud’s great downbeats, and I put my keys on the organ and—nothing happened. Somebody had turned it off. And the switch was out in the hall. It still makes my face flush.

At the same time that Bud was founding CpM, the college choruses became much more serious, too. Harvard-Radcliffe and the Conservatory Choir under Lorna Cooke deVaron. Lorna Cooke DeVaron was a musician of wonderful musicianship and wonderful taste, but her strongest quality, it seems to me, was that she had a will of iron. She knew how to work the politics of the Conservatory, and if you’ve ever had any contact with the Conservatory you know that you have to be very clever in order to get your way. The Conservatory has always been negligent of the chorus (is the President of the Conservatory here? I do still teach there, so I have to be discreet.) Well, Cookie came in and established a standard of musicianship and of excitement in programming and a relationship with the Boston Symphony, which was incredibly important to the reputation of the entire Conservatory. Harvard-Radcliffe also shared that affiliation, with occasional performances with the BSO under Munch, and of course CpM. There was no Tanglewood Festival Chorus, so the conductor always had to come to a delicate balance as to which chorus to choose for which piece. I remember a performance of Berlioz’s Romeo et Juliette, the weekend that Much announced his retirement—that was kind of an exciting time.

Handel and Haydn and Cecilia had fallen into a serious decline in those years. But what has happened because of CpM and because of the rise in quality of the Conservatory and Harvard-Radcliffe, is that other schools in the area have taken choral music seriously, and community choruses have risen in quality very much. The Framingham Choral Society has been in existence for a long time, the Dedham Choral Society—Brian Jones conducted it for a long time. These groups all profited from a general increase in awareness and excitement about choral music. The situation has always been for the last 30-40 years that there are more qualified singers than there are audiences to hear them. But that’s anther issue!

Now we have many wonderful specialized groups—early music groups. I wish there were groups that specialized only in contemporary music, because I think there are singers who could staff that kind of group—a small group. And I wish there were more groups to explore the Renaissance—there’s room for more groups of that sort, too. There’s also room for groups that do a general repertoire.

The repertoire has changed, because those kind of programs that you’ll see in the programs I passed out that BJ Lang did in the 19th century would probably not be acceptable today. Critically they would come under some fire. But things have changed and they are going to continue to change—we’ll talk abut that later.

Richard Coffey

I loved that St. Matthew story. I conducted it for the first time ten years ago, and spent a lot of time preparing it, as we all would. And I as convinced that at the performance I would turn a page and say, “where’s that been all this time?” But I think we practiced it all.

Aly and I talked about whether my little paragraph should have a title and I said, “A Tale of Two Choruses,” perhaps. If it’s good enough for Dickens, it’s good enough for me. My topic early on assigned to me was to discuss the challenges involving auditioned groups, and so I will stick with that for a little bit. But early on to say that the auditioning part of that topic is not an immense distinction, really. Most of the challenges that I face as conductor of the two principal groups just named are not necessarily related to whether or not they are auditioned. The challenges are quite different, and that’s a topic for an entire other afternoon. But I will stick to the topic for a few minutes here.

As to audition—even the term—I don’t find it to be an exclusionary exercise. I find it to be a protective one, helping to ensure that a singer is not made to feel uncomfortable or out of place in a musical environment that is not a good match for his or her capabilities. That protection also extends to the group itself, in particular when it is an amateur group or a dues-paying group. Those who have signed up and signed on and opened their checkbooks are people of similar capacities and gifts and purpose, motivation, and really deserve not to have those efforts marred or diminished by the presence of persons not quite up to that particular task. There’s something Biblical about, “and there are many gifts, distinctions.”

So there’s the protection; we view it as a governor, perhaps. Protection for the music itself, and that’s the greatest of the callings. That is, the art and the experience.

So now auditions are called “try-outs,” did you know that? Yes, no more auditions, but people “try out.” I think it comes from the sports world, I’m not sure.

I conduct a third choir, Aly just named, besides CONCORA and besides the Chorale, and that is at the South Church in New Britain. The reason I’m naming it again, that’s United Church of Christ and American Baptist, the actually do get along, since they merged. Our mother church is Riverside Church, and we’re proud of that. Nonetheless, that is an auditioned choir as well. Now you say, should church choirs be auditioned? Well, my motivation, my raison d’etre for that is the same, that there is a high call, and that people need to meet a certain standard so that they are comfortable and so that the message is rendered very nicely. That choir has 32 volunteers and 5 professional leaders, and we actually cannot receive any more members at this point, there’s no more room. And perfectly balanced. And that’s because of the spirit that the audition provides.

We can discuss later the merits of auditions, and some of you may disagree with me in fact on that.

The other group that I have affiliation with is the Main Street Singers, a children’s chorus that South Church founded. It’s a non-sectarian, auditioned community children’s chorus. Dr. Mary Ellen Junda, I don’t know if you know that name, from U. Conn., in music education for quite some time, choral division, she’s the music director, but I’m her partner in that endeavor. There are some 60 children that, again, pass their try-outs by singing either one verse of America or Happy Birthday. At least it means that they’ll stand up and do something, and then they come in.

Just a quick history about CONCORA, you’ve heard it a little bit reviewed already, in that Hartford, where I’m from, is so very, very far away from you that you might have no idea about what goes on down there. Although I was really glad to see so many of you come down when that award was presented about two years ago.

CONCORA was founded by the South Church, where I became Minister of Music immediately after graduate school out of New York City. That was in 1974. It was founded by the church, I was very proud of this that they followed me; of course when I was 24 years old, they’d better (because when you get older they’re not nearly so intimidated). But in any case, to establish a non-sectarian professional chorus as cultural outreach by the congregation. It really had nothing to do with the Sunday morning choir (although there were some people in common). So—auditioned, and salaried. The church turned me loose to go find the money. And so that’s what we did. It still exists, and in 1985, we realized the name didn’t really describe who we were, we couldn’t go to certain funders because we were under the church umbrella, and so we became independent, called “Connecticut Choral Artists.” The church gave us their blessing to do that, we are still in residence there, our new pastor absolutely loves the fact that CONCORA is there, and so it’s a wonderful arrangement.

We do sing the works of Bach, mostly, and then we skip the 19th century in general, and then we pick up the 20th and now the 21st, as you would have commended us to do. Two years ago, we sang everything by Mendelssohn that we could find, so that was 19th century, but it was enough; we don’t do Verdi, we don’t do Wagner, we don’t dfo those. We leave those to other people.

The roster of CONCORA is 50, so that we don’t have people saying, “I’m a member of CONCORA but I never sing.” Because not everybody sings all the programs. We go out with anywhere from 12 to 42 singers, it’s more analogous to a symphony orchestra, where you have your array of auditioned and roster of string players, and if you’re doing Haydn you have a certain number, if you’re doing Mendelssohn you have a certain number, Mahler a certain number. So that is how that works.

The group CONCORA also has a quartet that goes into the public and parochial schools, called CONCORA-to-Go, SATB, helping young kids understand what a mixed quartet’s all about. It’s a world program, a big globe, they come touch and feel Ethiopia and then we sing about Ethiopia. That’s a very, very popular outreach program.

Then we have “On the Town,” a group of eight singers who do cabaret-style, very popular music. So we feel that we cover a great span of the repertoire.

Now let me jump from that group to the Hartford Chorale, already named. The Hartford Chorale is about to celebrate its 40th anniversary. I’ve been with them just at six years, and very happy to be their music director. I couldn’t have been more surprised to be asked to take that role on. The Hartford Chorale is the region’s principal symphonic chorus, so you see it that stands like a sister choir to CONCORA. I like to say that anything CONCORA doesn’t sing the Chorale does, and vice versa. So the Chorale, big-time 19th century music. We are the principal chorus with the Hartford Symphony, and we have also in the past few years been engaged by the New Britain Symphony, the New Haven Symphony, and others, sort of the “large chorus to go” down there.

That chorus, the Hartford Chorale, includes and eight-voice professional ensemble of section leaders. This model exists in other choruses throughout, if you go to the Chorus America membership page and website you’ll see—Philadelphia is a very good example of that, where the Philadelphia Singers provide the vocal core for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Chorus. And so that’s what we do. This “core” comes out of CONCORA—they’ve already met the standard—and they function in that very important vocal and musical role with this large choir.

The Hartford Chorale is now 180 members. I inherited 120, and loved them all, but when a new director comes along things change and there’s sometimes excitement, and also Edward Cumming, the music director, this is coming up on his last season right now, really liked what he had heard with CONCORA, and so he wanted to know when there was a change of personnel if I would take that position, because he sort of called the shots at that time, and I was happy to do that. So we grew from 120 to 180 within about 2 years.

So as to this topic—we have a triple topic today: Identity, Inspiration, and Innovation. I’ve used most of my time on Identity. I’ll go very quickly into Inspiration, the second topic. That’s simply from my point of view the music which we sing. For both of these groups, the intrinsic and inward inspiration that the performers experience while preparing and presenting the great music. The audience really never knows what goes on in the rehearsals, and perhaps they don’t need to. We just hope that we inspire them, but yet they don’t know that the major moments for us, when our hearts beat faster and the tears flow, are in the rehearsals, when there’s that wonderful moment, “we got it! we got it!” and then we say, “oh, thank goodness it happened in here in private.” And then we hope to take some of that with us to the stage. But as Robert Shaw (I sang with him for ten years) used to say, “You’ve got no right to cry on the stage. You’ve already go your crying done before you get up there. It’s the audience’s turn. It’s the audience’s turn to cry.”

Garrison Keillor told a Chorus America conference one time (all of these jaded conductors out there, 300 of us, convinced we had the answers to everything), “You do know the purpose of choral music, don’t you?” (Of course we’re sort of preening, like we’d sort of look funny if we didn’t.) He said: “to make people cry.” It was the same reaction, we all did that sort of laugh, then there was that, wham! but he’s right! And you think about it: The Brahms Requiem, any piece of music that you can name, the Faure that you’re going to hear next week, when you get to the Pie Jesu or the In Paradisum, the tears flow, it’s quite normal. And it’s a good thing.

And the final topic here, Innovation, of our three-part topic. I like to think that between CONCORA and the Hartford Chorale, the sky is the limit as to what we can take on. And I think that’s innovative. A week ago tonight... CONCORA sang seven pieces by seven conducting majors at the Hartt School of Music. Brand new pieces. Hard as heck! But we did it. It was an inspiration, I trust, to the students. I visited with each of them for quite some time. They visited rehearsals, we had conversations back and forth between the chorus and those composers, and then I invited them each to speak about their piece before we sang it, at the University of Hartford campus last week. Maybe you know the name Amy Feldman Berman—young people’s choruses sing a lot of her music. She’s the funder for that, it’s in her name.

And then the Hartford Chorale next month is giving the American premiere of the Stephen Montague Requiem, I don’t know if you know the name, an American composer but sort of a renegade living in England, a friend of Edward Cumming. It’s a very, very powerful piece. That, along with the Berlioz Te Deum, form the final program for the Hartford Choral this season, and it is in fact Edward Cumming’s final performance. It’s almost two months away, and I believe it’s already sold out.

Before I sit back down, just to say, the Hartt School is the home of the Fuller Arts Center. Does anybody have any Fuller brushes? That’s Alfred C. Fuller. He carried those brushes around himself in a case while he was building his big enterprise. Anyway, I’m like Alfred Fuller. I brought my brushes, except that they are brochures, back there on the piano, about Main Street Singers, about CONCORA, and others. Also, to mention that Chanticleer is singing tomorrow afternoon at South Church, where I will be.

Aly asked me some very good questions yesterday. I don’t know if she will present those again as we go around today, but if I said you’ll ask me those questions I’ll give you some answers. I’m honored to be here amongst these very distinguished colleagues. I know we’ll be talking about inspiration and vision, and so I hand this off to someone. Who’s next?

Nick Page

Singing is an act of compassion—that’s something central to my choruses, from the Mystic Chorale, and it goes back to the oldest song in the world. I want to teach you the oldest song in the world. It was sung by Lucy; in the Bible she’s that first mother, that woman we’re all related to, hundreds and hundreds of thousands of years ago. Would you all become Lucy right now? You’re all holding a baby, like this, and we’re going to sing a song to this baby, the first song ever sung—I did my research!—and it goes like this: “aaa” (audience responds aaa), and the baby went “ohh” (audience responds ohh), and put the baby down and looked up at the moon, and with a sense of awe went “oo!” (oo!) and the baby went “ooo” (ooo), and the mother was frightened and went “ahh!” (ahh) and the baby went “ah” (his voice changed [audience laughs]). The point is, if you go anywhere in the world, people sing all around the world. People let these emotions out through song. It started with the emotions coming out as vowels and grew into the drumming, and evolved into the music we have today.

We’re talking today about history, about legacies, and about the work. I studied with Lorna Cooke deVaron, and it’s something that changed my life. Francis Judd Cooke at New England Conservatory changed my life. Taught me to be a New Englander (if you knew Francis Judd Cooke, you know what that means). It’s that legacy passed on.

I had the privilege of working with a man named Chris Moore, who founded the Chicago Children’s Choir about 55 years ago in Chicago. For him, it was a legacy that lived on from his experience at Harvard University, singing with the Glee Club under Woody (the legendary Woody). What he loved about that experience was that there were no auditions. Everyone was welcome—with the assumption that you had to be amazing. OK? That’s a very important part of it: you have to be amazing. So he brought that philosophy to Chicago, during the civil rights movement, and he started the Chicago Children’s Choir, the first children’s choir with black and white kids together. Which was hard work because, if you say, “I want to have black kids in my chorus,” they’re not gonna come. You have to go and pick them up, and you have to bring them. It was hard work. But his vision lives on today, and now there over 6,000 children in the Chicago Children’s Choir program. All in schools throughout the city, it’s absolutely huge. So his legacy lives on.

A few years after leaving Chicago, I got to work with this amazing woman named Ysaye Barnwell. She is someone who leads songs, a song leader. She sings with a group called Sweet Honey in the Rock, women who sing African and African-American music. What she does in these singalongs is she turns a group of people who have never met before into a community. She does the oldest song in the world—“aaa”—and, like the music that all of us do—Fauré, all right? The spirit of God is in all of this music, it just sings out, and it’s part of that “aw”; it’s part of it.

From Ysaye Barnwell I was very inspired to bring in the audience and form this choir called the Mystic Chorale. And then I met Alice Parker, and she also changed my life because of her belief in getting people to sing.

So, the Mystic Chorale started in 1990. We are a non-auditioned chorus, which is why we have 100 altos. And 20 tenors. And the 20 tenors drown out the altos—don’t ask me why. We do three concerts a year—a fall and a spring concert that I conduct (two days, a Saturday and a Sunday), and then we have a guest artist, Jonathan Singleton, who comes in and does a Gospel concert in the winter. We have over 200 singers in our chorus, sometimes as many as 250. We make professional-grade recordings—this is our 20th anniversary, triple CD, 57 amazing songs. We have professional artists doing our artwork—here is our upcoming “Over the Rainbow” concert—pass some fliers around. We’re mainly a volunteer group, we have two paid people—three, including the accompanist (myself and an administrator). We have an amazing Board, two of whom are here today, and they work their buns off to make sure things work. They also have a group that says—when I come to them and say, “I want to do a concert where we all get into inflatable balloons and go off in the air”—they’re the ones who say, “no.” I transcribe or arrange most of the music that we do. The music is drawn from folk, it’s drawn from World music, this fall we’re going to be doing a Bluegrass concert. Next year we’re going to be doing a “Missa Eclectica” with movements of the Mass from all around the world. So, we do a whole mix of music. And we have a jazz band that we work with, instead of an orchestra (or, in the fall, a Bluegrass band). We have a lot of soloists. Everything is sung from memory—always. We do occasional things at nursing homes and senior centers. We have toured Europe and Central America, and we like to go to New York occasionally to perform there.

We are part of a growing “alternative choral” music, of which there are choruses all over the place. Groups in Vermont like Village Harmony and related groups that do shape note music, Bulgarian music, South African music, and do it very authentically—very, very much a living music. Groups like Chris Eastburn’s group in Arlington, called Family Folk Chorale—5 year olds to 80 year olds, singing mainly folk music (last week they did a concert of music by Bill Staines). Groups that I’ve met all over my travels—in Ireland [inaudible] that are based on the oral tradition instead of from the written page.

People like Bob Kidd, who died two weeks ago—I dedicated my song book, “Sing With Us”, to him. He was a man who, every day in his elementary school in Norman, Oklahoma, it started with 15 minutes of singing, the entire school. Francis Judd Cooke, my organist growing up in Lexington, Mass.: every Christmas he would have the congregation come a half hour early, he would pass out the Hallelujah Chorus and he would teach it to the congregation, because, he said, your number one choir is always your congregation.

So that’s the legacy that I come from, and I feel very blessed. And that’s all I’m going to say for now.

Johanna Hill Simpson

Lorna Cooke deVaron celebrated 90 years of life last year, and her advice to me was, “never conduct sleeveless.” That was 30 years ago, for my Masters recital. Priscilla French, who, as you know, conducts up in Portsmouth, had a gown made for her recital that was sleeveless, and she came to show Lorna—Mrs. deVaron—her dress, and she said, “oh, no never; you’ve got to put sleeves on that. Nothing is more unattractive than the back of a woman’s arms.” Anyway, that was one of the things that she taught me. She was also, though, was a real good fosterer and inventor and pioneer and bringer-on-er of new music and composers; so as graduate students we were in lots of scary situations with her.

I was thinking about what to talk about. Aly wrote in an email that I’m supposed to speak on developing young singers and directors who will carry the arts into the future. It’s been a busy week—I’m getting ready to go to Arizona tomorrow and I’m thinking about how many jeans I’ve packed and if I have the right coats, but, really, I kept thinking, well, duh!—what can I tell you except: children are the future. We could all go to our cocktail hour right now—but they’re paying me so much for this, so, here we go.

Another person who advised me, or who really helped me see a lot of clarity in my performing philosophy, is my colleague for about 14 years, Nancy Walker, who ran PALS with me side by side. I don’t know if you know her, but you’re only as good as who you run something with, your accompanist and your partner. She would always tell the children—and I would too—something very similar to what you [Richard Coffey] said, that “you are not the birthday child today.” It’s not about you today, it’s about you [pointing out]. As I’m making up this talk today, I keep thinking, it’s not about me, telling about me, it’s about what I can tell you that might be useful, affect you. The children always know that—its not about them—that’s why they always like to talk about what happened to the audience while they were singing. Since they are memorized and able to see out of the corner of their eye, there’s a lot of things that you see the children do that they get to see and they say, “oh, did you see that woman in the second row? She was sobbing.” Or, “that really made them laugh there,” or, if they didn’t, “it was so quiet.” That sort of thing. They really did notice what the gift they are giving. So, anyway... I’m preaching to the choir—so to speak.

How many of you have ever worked with children? Raise your hands—that’s good. And how many of you have sung in a choir in the last year or so? How many of have conducted in the last year? Lots! How many have grandchildren who sing in a children’s choir? That’s nice, I like that. And how many people have given money to a children’s choir? I like that, too. Anyway, I just wanted to know who you were out there.

So, I’m talking about creating a children’s choir. And not just any old children’s choir, but one that’s going to cause the children to have memories that will cause this addiction—this benign, fabulous addition to needing to find and recreate and re-form and revisit that experience for the rest of their lives. Listening to all of you talk, I know we don’t have any problems with singing people right now. Look at 200 people with you [Nick Page], all the people with you [Richard Coffey], and Cecilia, and people wanting to audition and not getting get in. You have plenty of singers. We have a pretty good audience, but that’s because the singers’ friends are required to go. Pretty much—except for a few cases. There are some very high-level choruses, choruses where people go who aren’t even related. I used to tell the children that as well as, if we could ever be so good that people are in the audience who are coming just to hear you and not because they’re in your family, then we’re really are on a roll—because then we know it’s their birthday and not our birthday.

I would like to talk about a few bits of my philosophy, if you’re going to support a chorus. We do have many fine ones in Boston—we are not poor in that regard. We have a wonderful children’s chorus, the Boston Children’s Chorus, that was started in my later years of directing PALS. Their mission was basically to unite communities. They started out with a wonderful visionary, Hubie Jones, and he was able to get lots of support and lots of children, and they’re doing a super job, and fulfilling that mission beautifully. We have the Boston City Singers, who do that also, but they are a little more globally oriented, and more ethnic music oriented, and they’re a little bit more “boutique” than this overall huge juggernaut. I think the Children’s Choir of Boston was modeled after the Chicago Children’s Choir, and they’re doing super. And, of course, we have this perfect choir named PALS—it’s not perfect, that’s why I love it, actually. They’ve been known, I think—if I had to give an identity to PALS, and I’m really not trying to pride myself, really—as “the artist’s choir.” It’s the one that grownups like to work with. It’s the one that sees things—that children are not children, they’re just miniature artists, that learn differently than grown-ups but are able to... that seems to be what they are—at least I’ve always thought so. And we don’t demand a lot, either, of other organizations.

You want to make a choir that creates heightened experiences for children. I’m so not happy to behave and perform safe things. I would so much rather create this incredibly safe environment for taking huge risks—whatever risks you feel like doing. Since I’m about to go riding in Arizona on a horse for a week: One of my most heightened memories is when we were in Montana riding a horse on this place called Big Horn, a long cliff, truly dangerous, truly frightening, but kind of challenging. We finally did it, and I’ll never forget it. It was terrifying, and wonderful, and when I’m 90 or when I’m 100 I’ll think back and go, “when I rode Big Horn, that was great.” I’m kind of thinking that music is similar. Some of the best experiences that make you search for more are the ones that are the most scary. So I would like a children’s chorus to be “out there”—and also to worry very much about children and their iPods and their iPads and their Facebooks and their way of not really talking but of texting and of not communicating face to face but of listening and watching things and concerts on YouTubes; and it’s almost like they almost think they’ve been to a performance by seeing to it on a little teeny screen on their iPhones on YouTube. That’s dangerous. We’re all getting along—we don’t really need to worry about that. But we do, actually, because to continue to foster direct communication versus electronic, hidden communication I think is a challenge, and those are the children that we’re trying to lure in and addict to our art that we’re all so passionate about.

So, how do you make it—how did I do it (its all about me, right?)—how does one make a children’s choir cutting edge, rather than just by the book? You’ve all heard very good by-the-book children’s choirs, if you go to ACDA conventions—especially older ones, they’re just these perfect, impeccably trained, predictably repertoired children, who are just... first of all, they kind of make me feel inadequate, and then they make me feel a little glazed over, often, and then you’re just not sure that this is the right thing for you. Thinking about inspiration: One year when I maybe was about 26 or 25, in Boston, I went to Sanders Theatre and saw the Tapiola Children’s Choir. Do you know that choir? It’s just the best! It still is just wonderful. All these children in these awesome Marimekko dresses and cool vests playing instruments and singing and moving all over the stage and singing so well, not just “playing around.” (I’m completely in love with excellence. I fell in love with my husband because he sang a solo at a concert; I’d never met him before, he was so excellent, but he was mine for 35 years! He was just so good.) They were just beautiful—visually, musically.

And then I went to an ACDA once and heard Henry Leck’s choir sing. They sang a song by Malcolm Davösch, the Kilanto, which became a very popular song to sing. I was sitting there, ready to be impressed, depressed, and glazed, a little bit. And they started using their hands. And they had tambourines and they had ribbons, and by the end, they were frozen, up like this, and to see children with their hands up in the air, there’s something that can make you cry, it’s just so beautiful. And so I took that away with me.

There was another thing when the Chicago Children’s Chorus came to sing with the Boston Children’s Chorus. This was well into PALS’ years and I was well into my own philosophy, but I was watching them in that room at Jordan Hall for the dress rehearsal. There wasn’t just (I can’t remember the name of the conductor, Jo something) this fabulous conductor. But there was a choreographer, a professional, who was watching the movement of the choir as it shifted and changed to reflect the music they were singing. There was a singer, a vocal coach, that was weaving in and amongst the children, modeling her voice or listening and making sure the blend was right. There was an accompanist, and there was a percussionist, and there was somebody watching just how they were standing, not just moving, but how they were walking in and if their lines were correct. There was a staff of thousands, all about making it so that the audience was just slayed—in the best possible way.

So, those are my three choirs that so affected me.

I think that in a children’s choir, I used to get—um, criticized—for not teaching enough about music literacy. I thought about PALS, and one of our philosophies at the beginning was to teach drama and dance, because if you’re singing and you don’t know how to act and you don’t know how to move, you’re wooden, and you’re not really a performing artist—which is what PALS stands for (“Performing Artists at Lincoln School”). You’re a choral... almost a puppet; you’re just repressed, and not really expressing yourself. So, right from the start we had an hour of choral music, and, one day a week, an hour of dance, and one day a week, another hour of choral music and then an hour of drama. Right from the beginning. Without the sense of being a dance group (well, at the end we did a musical). That was important to us. And we sacrificed musical literacy for that, because that was all the time we had. I kept thinking, I’m the teacher, they’re good ears, they’ll learn it, I’ll teach them how to follow scores, a lot of them take voice lessons, piano lessons, and instruments. I also encouraged an underlying—well taught by Mark Pearson and all my teachers at the Conservatory—pedagogy, but still, once you talk about movement and not pitch, I encouraged chest voice and that was [whispers] really bad, back then; and we went to an ACDA and premiered a new work by a Newton composer, Lynn Shader, and it was low, and there was like, ohh, that’s bad, that was really low—and I love low, so we kept doing that. And there was nasality, to reflect Bulgarian sounds or whatever, and I thought that was really good. I thought it was good where boys would go, “Jo-dee, my voice has changed,” and I went, “oh, that’s so good, let’s listen to how low it goes” [sings some descending scales]. We all celebrated—“everybody, listen to how low Keith’s voice is.” And then: “now sing high.” And then we’d develop a falsetto in the boy and have him singing with you, everything, highs up to G’s and A’s, and they were beautiful falsetto voices, and they went on to sing in their a cappella groups in college and became the stars because they could sing cool things.

I also think you should rehearse in interesting ways. When Aly first took over, she stood them up with music stands in a circle. And I went, woh, that’s great. There they were, children standing with their music and their music stands, becoming even more powerful and confident and professional and ageless. Not just little children sitting perfectly in their chair. I loved that, what you did there, and I hope you still do it.

I thought uniforms really mattered a lot. You had to make them look like the Tapiola Children’s Choir—really cool. So we made these Chinese shirts to go with the Tan Dun thing that we did at Symphony. Then we made another set that was supposed to be more angelic, Chinese shirts, for when we had to sing Damnation of Faust and we were those angels with Margarethe. It matter a lot how we looked. I thought, we couldn’t just have them look like, I don’t know, generic choir kids.

Finally—this is where I get into the scary part—things that nobody would say yes to, because they’re impossible, you can’t do them. I was in Arizona about four years ago and they called from the Symphony and said, “would you be interested in teaching about 25 children to sing the Sprechstimme in Moses und Aron?” I kind of knew what that was, but, really, not a lot. And I said, yeah, sure. And then here we were learning it, and it was very much fun, and memorable. The kids still know it, they remember it; I’ve forgotten it all, but I remember how scared I was.

Doing something like the Vietnam oratorio—“would you like to sing in Vietnamese?” OK, yeah, we would. And we found a wonderful woman who was married to Ronan Lefkowitz named Chen, who gave us all the Vietnamese pronunciation to make PALS suddenly so respected because we could sound Vietnamese. I have to stop in a little while and say, I get my nails and my toes done in a Vietnamese place in Brookline, and because of PALS I am treated like a queen, because every time I go in, I recite Vietnamese to them [recites lots of Vietnamese]; it’s all what we learned, and it was great.

Finally, the most important thing I think a children’s chorus of today needs to do—it needs to be funded for, and it should be encouraged—is composing, bringing new works into being. What could be better vehicles for that than children? Compared to us, much more compared to us, they are completely receptive to risk. They want risk. They’re not, “oh, goody, ley’s do something fun.” But they really do take very well to risk. They’re so quick to grasp what we’re trying to do, especially because, even though they’re looking and they’re guiding with their music and they’re looking at the score, they’re not really learning it visually. They’re learning it the real way, the way you [Nick Page] teach. They’re learning the real music part—how it sounds, what the text means, not what the words are and what the notes are doing. It’s incredible that way, how much more musical. And they memorize so easily, they have stamina to spare, as long as you can keep them focused; and we live (and I think Aly’s the same exact way, though actually I think she’s a bit stricter than I am) right on the edge between them completely falling apart and being completely right there, listening with hearts are on fire and their heads are icy, and at any moment they could just be terrible instead of just predictably good. I like that, too. They’re impatient, they’re open minded—anything sounds OK to them, really. They’re honest; when they’re not happy, they tell you, which is good because, you know, when I’m not happy I tell them; but they trust.

To close, I’d say, always keep your antenna up for composers. They are living really where you least know. They could be right next door to you. Last night I went out with a composer I’d never met. Does anyone know of Andreia Pinto Correia? She’s at McDowell right now, near where I live, and she’s writing things for the orchestra, she just wrote a children’s thing, she’s Portuguese and she just wrote for the Tanglewood Music Center—oh my gosh, is that exciting? There she is, about to maybe write a piece for my kids up in New Hampshire. When you’re working with a composer, or considering a composer, make sure you know yourself first and what you can stand. Don’t get yourself into a sound world that you really hate—and you can tell what the sound world is going to be by listening to the composer’s other works. I personally don’t believe in torturing an audience, but I do believe in challenging them. Know thyself when you’re doing that, and stay strong throughout.

The bond that you make with the children of trust, and of power—because it’s the power that you feel if you do a good job that you’ve suddenly made an audience change, you’ve communicated something, you’ve been a conduit between the composer, whether it was Bach or Mahler or Britten or Howard Frazin, or Dutilleux, or Tan Dun, or Mehmet Sanlikol, or all the people that we’ve worked with, you’ve suddenly been a medium, almost, between them and the audience. If you’ve done your job and the audience is obviously moved, upset, enlightened, delighted, or whatever, then you feel power. And when you feel that power, then you’re going to have it all your life. And that’s why we’ll always have children.

I hope that makes sense! Thank you very much.